Longlisted for The Booker Prize 2023 & The Authors’ Club Best First Novel Award 2024

Marianne is eight years old when her mother goes missing.

Left behind with her baby brother and grieving father in a ramshackle house on the edge of a small village, she clings to the fragmented memories of her mother’s love; the smell of fresh herbs, the games they played, and the songs and stories of her childhood.

As time passes, Marianne struggles to adjust, fixated on her mother’s disappearance and the secrets she’s sure her father is keeping from her. Discovering a medieval poem called Pearl and trusting in its promise of consolation, Marianne sets out to make a visual illustration of it, a task that she returns to over and over but somehow never manages to complete.

Tormented by an unmarked gravestone in an abandoned chapel and the tidal pull of the river, her childhood home begins to crumble as the past leads her down a path of self-destruction. But can art heal Marianne? And will her own future as a mother help her find peace?

Praise

‘Pearl, an exceptional debut novel, is both a mystery story and a meditation on grief, abandonment and consolation, evoking the profundities of the haunting medieval poem. The degree of difficulty in writing a book of this sort – at once quiet and hugely ambitious – is very high. It’s a book that will be passed from hand to hand for a long time to come.’

— The Booker Prize 2023 judges

‘Hughes’s novel, which is wonderful on the detail of a late 20th-century rural English childhood and at its best recalls Edna O’Brien’s masterful A Pagan Place, is radical in largely dispensing with dramatic tension in order to create a circling story that maps the lasting impact of a loss.’

— The Guardian

‘Pearl is a novel that has wisdom and experience distilled into it, that defies its downbeat subject matter with the joy of its telling.’

— The Times

‘Compulsive and wonderfully written, Pearl is a small gem.’

— The TLS

‘A quietly beautiful novel, full of grief and English poetry… A rare gem that fully deserves its Booker longlisting, and your attention.’

— The Telegraph

‘The prose has a bubbling verve that is deeply appealing.’

— The Financial Times

‘Vivid, haunting and a deeply satisfying read.’

— Nation

‘Pearl is a gorgeous, swirling, haunted and haunting potion of a book. It embodies like no other the truth that every absence is as singular and elaborate and mysterious as the presence of the thing – or person – it describes, no matter how back to front, inside out, lucidly or ethereally memories of its particulars may come and go. How utterly moving, to be under its beautiful, artful spell.’

— Paul Harding, Pulitzer Prize winning author of Tinkers and This Other Eden

‘If you love Kate Atkinson, you’re going to love this book . . . It is a pleasure to read.’

— Suzy Davies, Conservative AM

‘Siân Hughes’s voice moves us because she manages the difficult art of putting wit to the service of strong feeling – a rare achievement.’

— Hugo Williams

‘Haunting, compelling, beautifully written; translates mythic and literary undercurrents into a modern setting.’

— Bernard O’Donoghue

‘An utterly gripping psychological mystery.’

— Maureen Freely

‘A ghost story, a folk story, a story of loss and familial haunting, Sian Hughes’ Pearl is an enchanting and eerie exploration of how a child lays down the bones of an ancient past – a medieval poem – as a means of recuperating the voice of lost loved ones. A story about how we tell stories in the face of yawning gaps and deep sorrow.’

— Sally Bayley

‘It’s a beautiful, searching novel from start to finish – vividly told and movingly elegiac in its unfolding understanding of the psychology of loss. A terrific achievement.’

— Jane Draycott

‘Seamus Heaney award winner Hughes takes the classic text of the medieval poem Pearl as the root for this stunning debut.’

— The Sunday Post

‘Hughes’ writing is beautiful, full of details of space and place that give you the sense of being right by Marianne as she lives and breathes. The novel is written in the kind of first person narration that holds your gaze close to whatever the character experiences rather than tells us the story of their lives, with all its accompanying misdirection and philosophising.’

— Rym Kechacha

‘Stunning, enchanting and riveting, Siân Hughes’ Pearl is a treasure to read. Pearl is beguiling in its beauty and will leave you aching for Marianne and her family, as she unravels the story of her mother’s life.’

— Mirandi Riwoe

‘In Hughes’ debut novel about motherhood, there is as much wisdom as there is abrasion.’

— Jerry Pinto

‘It’s glorious and made me weep.’

— Annie Garthwaite

‘Wonderfully deft. The characters are extraordinary (the father is heartbreaking). Pearl was the best novel I read last year, and will remain a favourite.’

— Michelle de Kretser

Could It Have Been Written By A Woman?

Susie Nicklin

Just over forty years ago, I was offered a place to read English Language and Literature at Oxford University. (Getting that out of the way in the first sentence, as per the cliché.) I did what was called ‘fourth-term entry’, ie I took the institution-specific exams in the first term of my final year of school. The previous summer I had passed A and S level French, so I was only studying for two A levels and one S level at the time. My Latin teacher lived a 30-minute train ride away and I only saw her once a week; my focus was mainly on English, which is just as well because I contracted glandular fever at the beginning of that term and spent most of it at home in bed. It was there that I discovered a susceptibility to reverie; in the spirit of the late Marion Milner, it was a time with no boundaries, hovering in and out of the corporeal world. My parents both worked and my sisters were both at school, so as weeks stretched into months I learned about solitude and interiority, my erratic temperature creating visions and imaginary companions. Just down the road was the cottage in which Blake swore that Milton entered his left foot; why shouldn’t I experience the ecstatic, too?

I wouldn’t say that I developed an inward eye, and it wasn’t bliss – I was unwell, and a doctor came by regularly to give me painful penicillin injections (the conclusive diagnosis, which confirmed these as unnecessary, didn’t come until after they’d stopped). My fellow students were presumably out carrying on doing all the things which had caused my illness; at an assembly after my return the headmistress of my all-girls school (a comprehensive yoking the former grammar and secondary modern schools under one roof, literally, with ‘upper band’ and ‘lower band’ divisions) said nastily ‘There has been a lot of glandular fever around recently. You catch this through kissing. Susie Nicklin has glandular fever’, which ensured my return to scholastic endeavours was brief. In those days you only needed two Es at A level to be accepted to Oxbridge if you passed their own exams, so despite pages of flummery my letter of acceptance had specified I needed one E to get in, and not even my inability to conjugate Latin verbs rendered that unlikely.

By the age of 18 my accomplishments were limited. I could speak fluent French with a broad accent du midi and a fine ear for the demotic as well as alexandrines.

(I spent a summer in France just after my fifteenth birthday, working at a one-star hotel in Palavas Les Flots in the Gard, a departement I have loved ever since. I worked thirteen-hour days, seven days a week and they didn’t pay me because ‘that would be illegal, you are underage’. On Saturday nights we went dancing and got back at 0600 on Sunday mornings; four espressos later we started work again. On my first morning I asked a colleague if she’d ever visited England and she grinned, ‘Oh yes, that is where I get my abortions’. I agitated for a day off a week, which was eventually granted – well, they could hardly dock my pay – and then got grumbled at when others followed suit. The pocket money I had saved from up a Sunday job in a newsagent in Midhurst got stolen from my room, which I shared with four others, including the snoring grandmother of the hotel’s owner. I developed chilblains and varicose veins and a serious swearing habit picked up from the kitchen porters. It was glorious.)

I could understand quite a lot of Latin – I sang with youth choirs and the mass made sense, at least – and I had read a stupid quantity of books. During that French summer I got through most of Camus and even Racine. (Writing this I realise I must have been the most pretentious person in Bognor Regis. For a summer job after I left school I worked in the accounts department of Butlin’s tallying up sales of burgers at their sites around the UK, and read Russian novels on my breaks.) That was about the limit of my talents. I couldn’t ride horses, or swim, or play tennis, or sail, or ski, or drive, or sew or knit or paint, or even dance well. I played the flute and the piano to grade V but my hand to eye co-ordination was too poor to make progress. The only touch of glamour in my life came through my work as an usherette at Chichester Festival Theatre, where I met Laurence Olivier and presented a huge bouquet to Grace Kelly (in trials mine was the best curtsey).

When I started at Oxford I thought I’d be among peers (which, it transpired, I was, but only in the literal sense, as my tutorial partner was a punk and also an Eton-educated one-day-to-become-Viscount.) I’d already read some of the Victorian novels we would be studying in the first year and had packed everything on the list of required items (including a tea towel over whose design I’d agonised for days). After a sedate, sherry-fuelled freshers’ week – a far cry from today’s bacchanalia – I finally had my first tutorial.

Following some general chat my tutor said briskly:

‘Here’s the essay title for this week and the criticism you’ll need to research. See you next Thursday’ and I was perplexed. He said patiently,

‘As I explained, this week is Dickens. Next is Hardy, then Austen, Eliot, the Brontes etc.’

‘Which Dickens?’

‘All of them. And then all of Hardy. Eliot. Etc.’

I still remember the visceral sense of shock.

‘I’ve read two’ I ventured – ‘Our Mutual Friend and Bleak House.’

A hard stare.

‘You were sent the reading list in December.’

My sense of injustice was stronger than my nerves.

‘It just said reading list! It didn’t say they had to be read before we got here! I assumed that these were the books we would be reading! I remembered the tea towel!’.

He shrugged. The heir apparent smothered a snigger.

‘Well, you may have spent the summer inter-railing’ (all those bloody burgers! What price Dostoevsky & Tolstoy?) ‘but between now and next Thursday you will have read every novel by Dickens plus the necessary criticism. John Carey’s lectures are rather fine.’

And so began my second successive autumn term spent in bed, trying to keep warm, desperately hoovering up millions of words in shoddy second hand paperback editions from Blackwell’s, just across the road from my tiny, shabby room. Eight weeks in which I became disorientated, exhausted, almost hallucinating from inhaling so many plots, characters and locations. I worked in a local pub over the Christmas holidays and the whole Oxford thing felt like another feverish dream.

When I got back I realised that I hadn’t considered what I should have prepared. But it turned out that this didn’t matter because we were studying something totally different. We were entering the Anglo-Saxon and medieval worlds, full of allegory, legend, poetry, violence, ritual, rhythm. Finally, I was on a level playing field. No one had read any of this stuff before; you had to say the words aloud to make any sense of them and then it was a glorious riot of alliteration, bouncing rhymes, repetition, humour. A green knight! A green chapel! Camelot! Beowulf! I was totally enchanted. No more cramming under a cheap duvet; you had to study this stuff with the delightful Bernard O’Donoghue, a great scholar and poet. It made sense from the start; even if I couldn’t understand it all I found it exhilarating.

One poem in particular was unforgettable. The incantatory, transcendental, late 14th century Pearl, presumed to be by the author of Gawain and the Green Knight, in which the writer mourns the loss of a daughter who reappears in a vision. We argued it must have been written by a woman – so much attention to detail, so moving. I recommend the 2011 translation by Jane Draycott, with an introduction by the same Bernard O’Donoghue, published by Carcanet.

Perle, plesaunte to prynces paye

To clanly clos in golde so clere,

Oute of Oryent, I hardyly saye,

Ne proved I never her precios pere.

So rounde, so reken in uche araye,

So smal, so smothe her sydes were,

Queresoever I jugged gemmes gaye

I sette hyr sengeley in synglure.

Allas, I leste hyr in on erbere;

Thurgh gresse to grounde hit fro me yot.

I dewyne, fordolked of luf-daungere

Of that pryvy perle withouten spot.

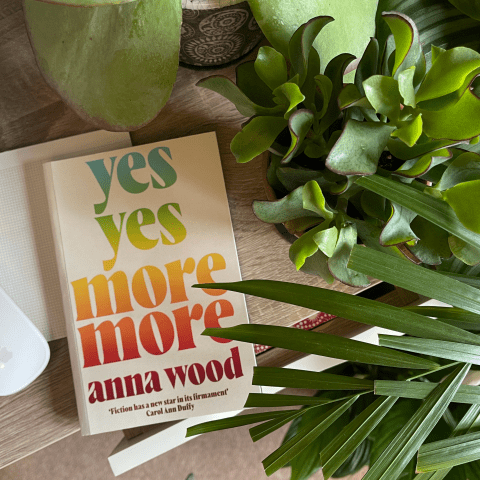

So when Peter Buckman sent me a manuscript entitled Pearl, by Siân Hughes, I was enchanted. Hughes’ writing is flawless, like the privy pearl without a spot; I hardly changed a word. She captures the spirit of the original and shows us consolation through legend, nursery rhymes, folk songs, as a daughter seeks to understand the reasons for the disappearance of her mother. I couldn’t be more proud to publish it at The Indigo Press, with an endorsement from Bernard, and we celebrated in Siân’s bookshop in Cheshire, just down the road from the green chapel itself.

And a footnote: just over a decade ago I led a global programme for the British Council, 264 projects in 62 countries over three months, celebrating the 200th birthday of Charles Dickens, and before the key UK event I nonchalantly briefed our CEO over cocktails prior to a big speech he had to give on the novels. All of ‘em.